News

True heroes to the country's freedom

Scott Wagar

01/28/2014

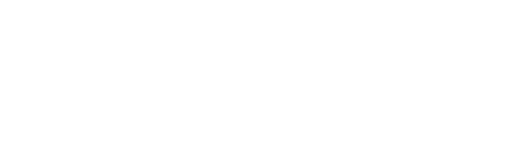

It was a photo found on a social network. It was a photo of two young men of Native American descent standing in a doorway dressed in double-breasted suits with spit shine shoes on the teenagers. There was also a caption with the photo which stated their names and that the photo was taken at the Wahpeton Indian School.

Although the photo was somewhat ordinary, the caption added an interesting sentence to the photo which made it intriguing, because it stated these two young men would go on to become soldiers and were “two native heroes” of their ancestors while fighting for their country’s rights and freedoms in combat zones.

The two young men were Frank George Gillies of Dunseith and Woodrow Wilson Keeble of Wahpeton. In their time in the service, one would give the ultimate sacrifice of his life, while the other would receive the Medal of Honor posthumously.

FRANK GILLIES

Frank Gillies was born on May 14, 1923, in Dunseith. He was the oldest child of John and Lucy (Davis) Gillies. During Gillies’ youth, he was raised on his family farm and attended the Indian Day School in Dunseith for five years. Gillies then went to the Wahpeton Indian School for three years before going on to graduate from high school at Flandreau Indian School in South Dakota.

At age 19, Gillies, who was a Chippewa Indian, volunteered for the Navy at the beginning of World War II and entered into the service on Oct. 18, 1942 where he was trained as a torpedo man on a destroyer called the U.S.S. Johnston.

The Johnston was a Fletcher-class destroyer. In the Navy, the ship was known as a “tin can destroyer” because it was considered a light ship when it came to its small size and limited armament on board. Its primary weapons included a number of rather small size 125 mm (five inch) guns and torpedoes.

The Johnston was laid down on May 6, 1942 by the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corp., in Seattle, Wash. It was launched on March 25, 1943, and commissioned on Oct. 27, 1943, under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Ernest E. Evans, who like Gillies was of Native American lineage.

The ship was ordered to the Pacific Theater and took part in battles during the Marshall Island and Solomon Island campaigns in the first part of 1944. In October of that year, the Johnston sailed to the Philippines to assist in that operation under the overall command of Gen. Douglas McArthur after his famous speech of “I shall return” after he was forced to leave the Philippines in 1942 after the Japanese invasion of that country.

After being supplied at Admiralty Island, the Johnston sailed on Oct. 12 with Taffy 3, one of three units of Rear Admiral Thomas L. Sprague’s Escort Carrier Task Group.

Their first task for the Johnston was to protect the escort carriers maintaining air supremacy over eastern Leyte and its gulf.

In the morning hours of Oct. 23, 1944, the Battle of Leyte Gulf started when U.S. submarines attacked units of the Japanese fleet coming from the South China Sea into a beachhead at Leyte.

The following night, the Japanese’s Southern Force (made up of battleships, cruisers and destroyers) was annihilated as it tried to enter the Leyte Gulf.

At around the same time, a larger Japanese unit, Center Force, came under heavy attack by Admiral William Halsey’s attack carrier planes, which made the Japanese turn around and retreat. However, the Japanese Fleet subterfuge Halsey, which in turn made Halsey move north with his aircraft carriers and battleships to attack a decoy Japanese carrier. With Halsey removed from the Leyte Gulf, this left the Johnston and its small escort unit alone in the gulf on the evening of Oct. 24.

With Halsey out of the picture, on the morning of Oct. 25, the Center Force made its way into the Philippine Sea and headed toward Leyte Gulf up along the coast of Samar with only the Johnston and its task units standing in its way.

On that morning, U.S. air patrol were out and reported to the Johnston that they were in the direct path of the Japanese Fleet, which was bearing down on them with four battleships, eight cruisers and 11 destroyers.

Evans went into action immediately and ordered his crew on the Johnston to place a smoke screen between the U.S. carriers and the Japanese force.

Being too far away to use its light guns, the Johnston broke formation, went through the smoke screen and went straight toward the Japanese fleet to get in range where the Johnston began firing at the enemy fleet.

The Johnston fired over 200 rounds at the Japanese, while Gillies and the other torpedo men of the ship sent all 10 torpedoes at it adversary before the ship went behind its smoke scene once again.

When the Johnston came back out of the smoke scene the second time, Evans saw the damage his torpedo men did to the Japanese’s heavy cruiser, the Kumano, which had its bow blown off and was retreating.

Celebrating its hit on the Kumano didn’t last long, because within a short period of time the Johnston was hit six times by shells to its bridge, which caused the ship to lose its power to its steering engine, along with a portion of its guns and render its gyrocompass unusable.

Although damaged, the ship’s men made repairs as best as they could and continued on with the fight. Orders were placed for the other American ships to conduct a torpedo attack. The Johnston, who wasn’t able to keep its position due to its damaged engine, and with no more torpedoes left, made every effort to move and fire its remaining guns successfully at the enemy.

Instead of retreating, the Johnston stayed in the fight and continued to lay down fire on the Japanese.

At one time, the Johnston saw the American carrier, the U.S.S Gambier Bay, under heavy fire by an enemy heavy cruiser and began firing its guns on the cruiser to draw the ship away from the carrier. The Johnston also shelled the cruiser four times.

As the battle continued, the Johnston continued to draw fire on enemy ships attempting to get the enemy to turn on its ship. However, as the battle continued, numerous Japanese ships set its dials on the Johnston and hit the ship a variety of times, destroying its last engine, bringing it dead in the water.

The Japanese ships then surround the Johnston and started attacking the ship from every side. As ammunition poured through the ship, it took out a forward gun, another gun and a 40 mm ready ammunition locker. With things looking grim, the men of Johnston kept fighting and asked for more shells to fire.

As they continued, Evans, who already had two fingers blown off in the battle, stayed steady and yelled orders to his men who were turning the rudder of the ship by hand.

However, the shots kept coming from the Japanese and as the end came to the Johnston, an enemy destroyer came within 1,000 yards of the ship and placed one final fatal shot into the ship which caused the Johnston to sink.

Of the 327 men on the ship that Oct. 25 day, only 141 were saved. Of the 186 men killed, around 50 were killed in battle, 45 died on rafts from their wounds and 92 men were able to get off the ship with Evans, but as they floated away from their ship they disappeared and were never heard from again.

One week before the Christmas holiday, the Dunseith Journal reported that Gillies had been killed in the battle. Gillies’ body was not returned to the family, but a memorial service was held in Gillies’ honor at St. Louis Catholic Church in Dunseith with family, friends and members of the American Legion in attendance.

WOODROW KEEBLE

Woodrow Keeble was born on May 16, 1917, in Waubay, S.D. to Isaac and Nancy Keeble. At a young age, the family moved to Wahpeton, N.D. where his mother was employed by the Wahpeton Indian School. Unfortunately Keeble’s mother passed away at a young age, but the family stayed in Wahpeton where Isaac enrolled all of his children, including Woodrow, into the Indian school.

Keeble, who was a full-blooded member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation, enjoyed sports, especially the game of baseball where he pitched for Wahpeton’s amateur team and took the team to 10 straight victories.

His talents in baseball were so skillful that the Chicago White Sox started to recruit Keeble, but World War II stood in Kebble’s way when his Army National Guard unit was called up to fight. However, his pitching arm would come in handy as a soldier, and he would save a lot of his fellow soldiers’ lives in the midst of battle because of his pitching arm.

Keeble was part of the North Dakota 164th Infantry Regiment and the outfit was sent to the Pacific Theater to fight the war. The regiment’s first battle was Guadalcanal and the 164th landed on its beaches in October of 1942 where they joined the First Marine Division which suffered a number of losses in their attempts to clear the island of Japanese soldiers.

For the 164th, Keeble operated a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) and used his pitching arm to throw grenades with exactness at the enemy, which assisted in saving lives of Americans and bringing victory to the Battle of Guadalcanal.

After WWII, Keeble returned to Wahpeton and accepted a job with the Indian Day School. He also married Nettie Abigail Owen-Robertson in November of 1947.

In 1951, the 164th was reactivated and sent to the Korea War. The men trained at Camp Rucker in Alabama before moving on to Korea. While at Camp Rucker, the commanding officer had to select sergeants for deployment to the front lines of Korea and decided to do so by drawing straws. Keeble refused to draw straws. Instead, he volunteered because he felt that with his experience in WWII he could teach the younger soldiers how to fight in combat.

Keeble was assigned to George Company, 2nd Battalion, 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division, and with his combat experience and leadership ability he was quickly promoted to Master Sergeant and leader of the 1st Platoon.

As the company went into combat, it was ordered to the central area of the Korean peninsula to capture a series of steep mountains where the Chinese were utilizing the town of Kumsong as a supply depot.

The operation, which was called the Operation of Nomad-Polar, started on Oct. 15, 1951, and lasted for six days straight. During the battle, Kebble was wounded on Oct. 15 and then again on Oct. 17, 18 and 20 for which he was given only one Purple Heart. For his actions on Oct. 18, he was awarded the Silver Star, but his action on Oct. 20 would one day grant him posthumous the Medal of Honor.

Oct. 20 was the sixth day of fighting for George Company and as Kebble arose that morning he was suffering with two gun shot wounds to his left arm, a grenade wound to the face which almost tore off his entire nose, a twisted knee and a concussion from a grenade. The night before, physicians removed 83 pieces of festering shrapnel from Kebble’s body.

As the battle for Hill 765 was to start, and deeply entrenched with Chinese soldiers, Kebble was ordered to stay back from the battle, but he refused to let his men go alone and led them into battle.

As he lead his men that day into battle, Keeble saw that American soldiers had become pinned down by three well fortified machine gun bunkers.

Without any regard of his own life, Kebble rush to the pinned down soldiers and then crawled forward to the first machine gun emplacement. As the Chinese trained their gun fire on Kebble, he used his pitching arm from his baseball days and threw a grenade directly into the bunker and took it out completely.

Keeble then moved forward on the second emplacement and directed another grenade in the bunker and destroyed that one.

He continued up to the third emplacement, this time with a heavy barrage of gun fire and grenades raining down on him from the Chinese, but Keeble once again destroyed the last bunker with complete accuracy of a grenade that he threw at the emplacement.

Keeble’s men then started moving forward up the rigid mountain side as Keeble laid gun fire down on the enemy where he caused heavy causalities.

From there, Company G gained an important objective of the battlefield, all due to Keeble’s brave fighting.

Recommendations were made three times for Keeble to receive the Medal of Honor for the feats he did that day, but the recommendations were lost twice, and the third one was turned down due to a technicality of regulations that prevented the third request to move forward.

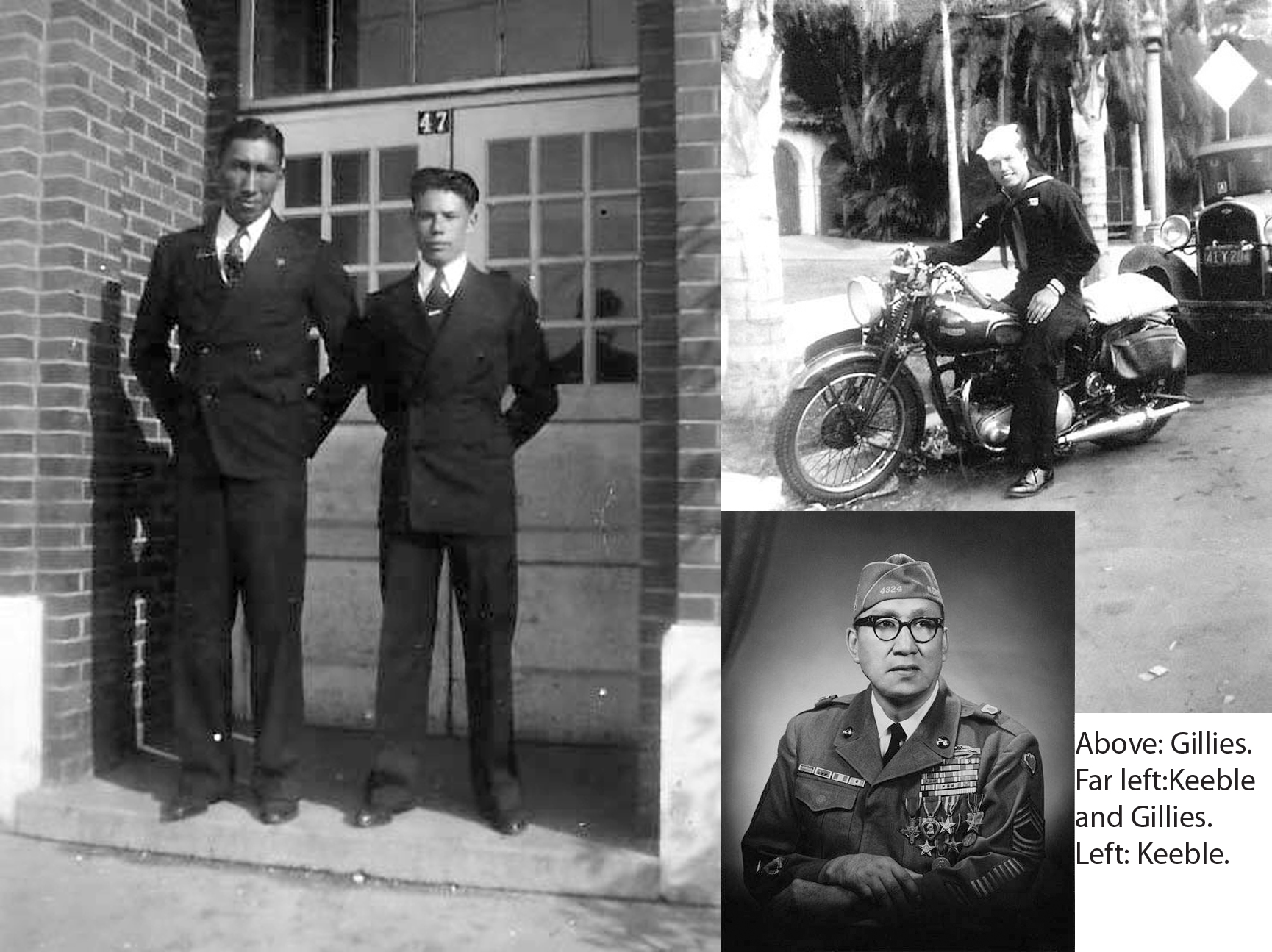

For his bravery in combat, Kebble was awarded the Purple Heart (twice), Silver Star, Bronze Star for Valor, Bronze Star for Merit, Combat Infantry Badge (first and second awards) and the Distinguished Service Cross.

After the Korean War, Keeble went back to Wahpeton and to his job at the Wahpeton Indian School. Soon after he returned home, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. He was sent to Minneapolis, Minn, for treatment which ended with doctors having to remove one of his lungs, which caused a series of strokes that left him with the inability to speak, partially paralyzed and he could not work the remainder of his life. His wife, Nettie, passed away a year later, leaving Keeble to raise his son Earl alone.

With his illness, Keeble fell on hard times and he had to pawn his military medals for money. But, with the determination he had lived his life by, he moved forward in life, married Blossom Iris Crawford-Hawkins, the first Sioux woman to earn her Doctorate of Education.

On Jan. 28, 1982, Keeble passed away and was buried in Sisseston, S.D.

Sadly, the Medal of Honor alluded Keeble in his life, but family and friends in honor of him worked hard to make sure he received the medal.

Through assistance from Sen. Byron Dorgan, D-ND; Sen. Kent Conrad, D-ND; Sen. John Thune, R-SD and Sen. Tim Johnson, D-SD, Keeble’s family was granted Keeble’s Medal of Honor posthumously by President George W. Bush through an Act of Congress on March 3, 2008.

Two years prior, Conrad and North Dakota Adjutant General Michael Haugen presented Keeble’s family with a duplicate set of his medals he had to pawn at the Wahpeton Armory.

The photo of Frank Gillies and Woodrow Keeble on the doorstep of a building at the Wahpeton Indian School is an extraordinary photo of the two Native American boys who would grow up and go on to give everything to their country.

The caption in the photo is truly correct, Frank Gillies and Woodrow Wilson are “two native heroes” for their people and for their country. They are individuals that should be remembered at all times in our country’s history for the feats they did for our nation.

Writer’s Note: Sources for this article came from the Gillies family, LaVallie family, the Dunseith Journal, Wikipedia and the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.