News

San Haven's history in saving lives with TB

Scott Wagar

10/23/2012

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Bottineau Courant is starting a series which looks at the history of San Haven, North Dakota’s only state run sanatorium, which was operated in the Turtle Mountains for the majority of the 1900s. This week, the newspaper looks at the beginning of San Haven.

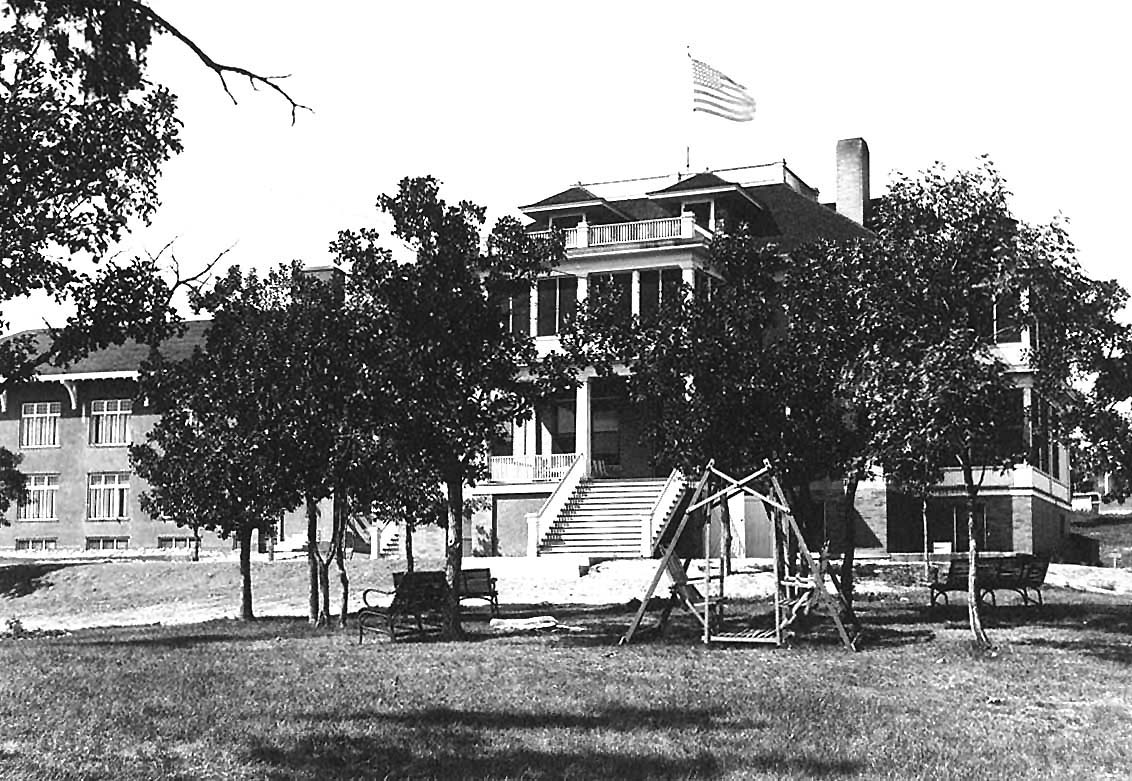

In November of 1912, San Haven opened its doors for patients with tuberculosis with great anticipation of curbing the death rate of tuberculosis in the state.

The first building to be constructed on San Haven’s 260 acres of land was the Administration Building at a cost of $25,000. The structure housed a central dining room, kitchen, laundry, furnace room, employee’s dining room, porches and dressing rooms for 18 patients, offices, a laboratory and living quarters for the superintendent’s family and nursing staff. Initially, the building did not have electrical lights or telephone.

Dr. J.P. Widmeyer of Rolla was the first administrator of San Haven and in late November of 1912 he welcomed the first patient to be admitted into the TB sanatorium, Martha Magnusson of Wildrose, N.D.

In 1912, it cost patients $1.50 a day, or $5 a week to be treated at the facility. Patients could either pay the sanatorium bill themselves, or, if they did not have the means to pay, the counties in which they came from would care for their bills.

In the first 18 months of the sanatorium opening its doors, 170 patients had been admitted to San Haven with a long waiting list for individuals wanting to get in to be treated.

With San Haven filled to its capacity, and a long waiting list, the institution constructed three cottages for the patients in 1913, which included the Men’s Cottage, the State Cottage for Women and the Masonic Cottage, which was funded by the Masons and furnishing by the Order of the Eastern Star. Outside of the three cottages being built on the property, the state also constructed a cottage for staff members that same year.

In 1915, the state added another cottage for the superintendent and his family, along with a dairy barn and new a structure called the Refractory Building which housed a new kitchen, dining hall, assembly room and dormitory for employees.

With victims of TB coming to San Haven to be treated, family members of the TB patients often moved to the Dunseith area to be close to their loved ones while they were being treated. Other individuals journeyed to the sanatorium to find employment. With an increase in population and construction going on at San Haven, enterprise also increased in the Dunseith area, which included an interesting team of horses owned by a Dunseith man.

“Supplies were hauled from town by Henry Grim, driving a grey horse team of communistic habits. These horses wrecked much property. It was not unusual to find boxes of groceries, wagon wheels and bits of horse hair along the two miles of sanatorium road,” stated Stephen L. McDonough in his book, The Golden Ounce. “The grey horses were sold for a good price during the World War (WWI) and shipped to Europe. Everyone sighed relief when the news came that they were blown up in the Battle of Marne.”

As for San Haven, itself, any resident from North Dakota could be treated at the sanatorium. Patients were admitted to the San when their personal physician or county medical health officer diagnosed them with TB. At that point, the superintendent of the sanatorium would be notified, and if there were any open beds at the institution, patients would be allowed to come to the facility.

Once diagnosed, patients primary treatments during their stay at the sanatorium consisted of rest, fresh air and a well balanced diet. Patients, depending on how severe their tuberculosis was, could expect to be in the sanatorium from one to four years.

Patients spent the majority of their time outdoors receiving fresh air treatments, even through the winter months. If indoors, patients’ windows were always left open, no matter what the weather conditions. For patients who slept in the Administration Building’s porches, it was not unusual for them to wake up in the morning in the wintertime and find snow on the porches’ floors. To keep warm, the patients slept with numerous blankets and hot water bottles.

According to Dr. John Lamont of Towner, who replaced Widmeyer three months after the sanatorium open, the improvement of the patients’ health at San Haven was found to be successful from the very beginning.

“The majority of the patients have shown a great improvement in health, the average gain in the first 50 patients treated being about five pounds, and this is in spite of the fact that many of our early cases sent to the institution were in the advance stage of the disease,” wrote Lamont in the Biennial Report to the Board of Control of State Institutions for the Period Ending June 30, 1914. “The largest gain was thirty-three and one-half pounds.”

Even though the state was getting a handle on TB through San Haven, there was still no cure for the disease, and it flourished in the state with alarming numbers, bringing an abundance of patients to San Haven, along with a number of new buildings and treatments for tubercular patients.