News

Looking back at county's history in the oil industry

Scott Wagar

02/28/2012

Editor’s Note: Presently, with so much discussion taking place within Bottineau County about the future of increased oil production in the county, the Bottineau Courant has decided to publish a two-part series on the history of Bottineau County’s first oil explorations and its first oil boom. This week, the Courant looks back at the first explorer of the county’s oil resource, George White, and his incredible journey to find black gold.

If one looks back on the history of oil exploration in Bottineau County, the name George White takes the top spot in the county for the work he conducted in attempting to find oil.

White was born in Stratford, ON, in 1864. He homesteaded in Bottineau County in 1899 and filed a claimed in Whitby Township in the Souris area.

His first venture into North Dakota was a sojourn which would stay in his memory’s eye forever. In 1877, he traveled to St. Thomas, ND, to visit his cousin, Allen Iman. Within days after arriving, a thunderstorm developed which took a straight path at the Iman’s house in which Iman’s 17 year old daughter was killed, while the remainder of the family was found unconscious in the home.

White stayed on and assisted his cousin with the fall harvest before returning back to Ontario. At home, even with the terrible tragedy of his family still on his mind, White, a true adventurer, couldn’t get the west out of his mind. The next spring, White, and his brother, Norman, made the decision to go west. They boarded the Colonist train in March of 1889 and traveled to Deloraine, MB, with the goal of finding land to farm. (The Colonist train was operated by the Canadian Pacific Railway to transport new settlers to the western part of Canada. The settlers were transported in what the CPR officially called the “Colonist cars.”)

However, unable to find land to claim in Deloraine, the White brothers heard of homestead land in Bottineau County and made their way to Bottineau by foot, walking over 30 miles from Deloraine to Bottineau.

There the two brothers homesteaded land on April 22, 1889, filing adjoining claims in Whitby Township.

By 1900, Norman found North Dakota not to his liking and moved to California.

White, on the other hand, enjoyed the state and saw great success as a farmer and livestock holder. His homestead claim of 50 acres in 1889 grew to 3,700 acres by 1917 with a 52 man threshing crew to assist him in harvesting his fall crops.

White also had livestock, which consisted of a large number of milk cows and over 600 head of sheep.

His adventures on North Dakota prairie also led him to oil exploration in the Souris area starting in 1926.

Through the time he spent on the land, White had discovered sandstone out-croppings, a sign of oil formation.

Excited about the possibility of finding oil, White went to work to sell his dream to the area people in hopes of finding backers through shareholders. However, a number of local individuals disagreed with White about the possibility of oil formations in Bottineau County, including his brother Herbert, who was a geologist in California. But, White was a determined man, and at the age of 62, he moved forward in finding oil.

White’s first order of business was to contact Herman Bollinger, a Souris native who had worked for White as a farmhand in his teenage years, and, who had just returned from Canada where he had worked as mechanic and had a few dollars in his back pocket.

“I ran into George White and he wanted to go into the oil business. So, I invested and helped him there. The first thing you know, I’m a driller,” said Bollinger at the age of 88 during an interview in 1984 for the Bottineau Courant’s Centennial Edition. “He (White) was quite a plunger. If he got an idea, by golly, why he’d be one to have to work it out, no matter what the idea was. Of course, a lot of things didn’t work out for him, but he laughed and said to me, ‘Herman, I get a kick out of doing these things, but sometimes I just get kicked in the pants.’”

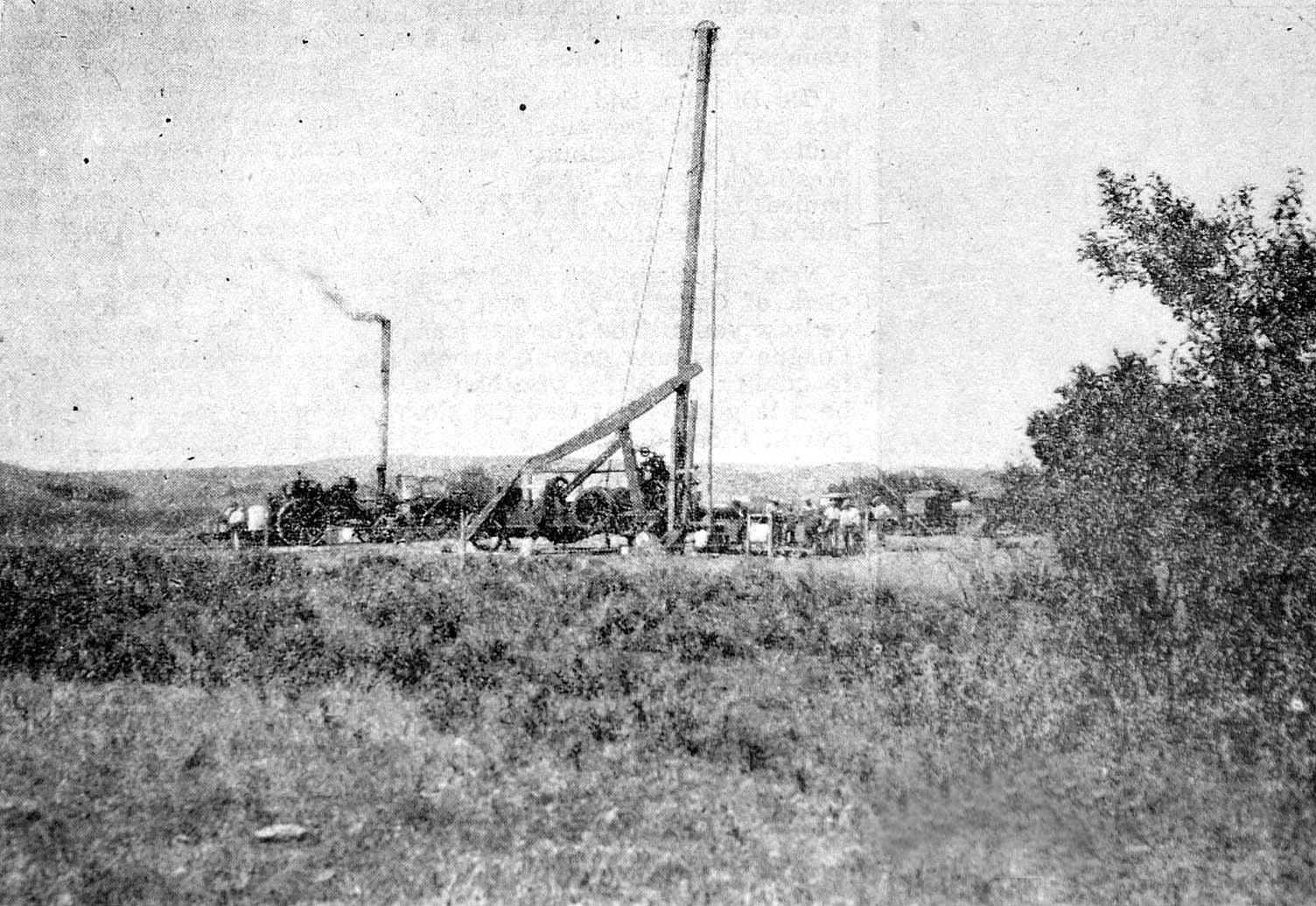

Besides Bollinger, White’s brother, Arthur, Dr. A.R. McKay, August Frykman, Knute Olson and a number of other backers invested the $10,000 White needed to purchase a drill from the Star Drilling Company out of Akron, OH. The drill, along with two men who would operate the drill, all came to Souris by the Great Northern Railroad.

To pay for labor and equipment, N.F. Synder, a Bottineau farmer, sold stock for the investors’ company, now called the Turtle Mountain Oil Company, which sold shares in the company for $10 a piece.

White staked out a claim on Ole Torhol’s farm, which was five miles northeast of Souris.

With the company set up, equipment in place and employees at hand, everybody was ready to begin, but the first few weeks of Turtle Mountain Oil’s venture didn’t go as White had planned. The drilling started in May, and within days the two Ohio drillers started arguing about the best way to drill the well. Their disagreements became so out-of-control one of the drillers quit and left the site.

Down a driller, White turned to Bollinger, and in short order Bollinger was trained as driller by the remaining Ohio driller, Jake Miller.

Bollinger and Miller operated a coal-fired boiler with water that was fed by a local stream. Local individuals were hired to stoke the fire around clock because White made the decision to work two 12 hour shifts.

Miller worked the day shift, while Bollinger worked the night shift. Bollinger and his wife, Marion, also pitched a tent on the site and lived at the rig site throughout the summer and fall. Marion also cooked the meals for the crews out of a cook car owned by White, which he used during the threshing season.

When it came to the equipment, Turtle Mountain Oil started with a 24-inch drill stem which held a five foot bit. The bit would be placed in the ground and then lifted out while the dirt mixed with the water and sand. The stem would come up next and a baler was placed in the hole to collect and remove the mud. The crew then placed steel casings into the hole to support the walls of the shaft.

Fortunately, and unfortunately for the crews, the earth was soft in that area of Souris, which made drilling easier, but caused the walls to start caving in the further they drilled down.

At 150 feet, the 16 inch casing the crew was using struck a ledge, causing a bend in the casing. The casing was straightened out, but the damaged caused water leakage and made the walls cave in more.

The crews then used the casing to push through the ledge by lifting and dropping the steel pipe until it broke through the ridge, but in doing so the shaft had to be frequently narrowed as they went further down into the ground.

At 900 feet, the crews spent most of their work days removing water from the hole. The crew also struck natural gas, but it was a category gas that wouldn’t burn.

From 900 feet down, the crews had a number of breakdowns and the rig was officially shut down at 1,000 feet on Jan. 27, 1927.

White went back to his farm in January, but with his intuition telling him that oil was under his rig site brought him back to the site that summer. Although, he had one problem, he had no money which to invest to get the rig and company operational again.

However, White’s established an idea where he advertised a public picnic at the rig site which featured a bowery dance in the evening and the selling of shares for $10 a piece with the assurance that all investors would be “millionaires.” (The bowery dance was a dance that began with the band playing half of a song with the dance floor empty. Individuals would then go around and pick up nickels from anyone who wanted to dance. Giving a nickel allowed a person to choose their partner and dance for the rest of the song. The money was donated to the evening’s cause. The dance originated at “The Pavilion” at Union Park in Dubuque, IA.)

During the day of the picnic, over 300 people showed up with around 100 individuals becoming shareholders. White worked the crowd with what locals called his charming personality through the picnic and evening dance, and by night’s end he had enough money to make the rig operational once again.

Bollinger and White were back in business that summer and they drilled down to the 2,250 feet mark, but, the drill came up empty. No oil was discovered and the rig was shut down for good.

Although White never hit oil in Bottineau County, oil was discovered in the county in 1952 starting the first oil boom in Bottineau County.

Remarkably, in 1955, two miles from White’s site, oil was discovered in a formation 1,000 feet from where White and Bollinger stopped drilling in the summer of 1927.

“If we would have gone down another 1,000 feet we would have struck oil,” Bollinger stated in 1984. “Maybe we weren’t so crazy after all.”

Additional Note: Next week, the Bottineau Courant will write about the discovery of the first oil well in Bottineau County, its boom and how it affected the county.